A new twist in a long road

Posted: November 28, 2021 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: brighton, domestic abuse, feminism, history, local government, rise Leave a commentI’m currently reading this book about the history of the women’s refuge movement. Its subtitle is “We’ve come further than you think”. As the author, Gill Hague, explains in this taster article, the first women’s refuges grew directly from the second-wave feminist movement, and they were nothing less than revolutionary:

“At the time, they were new to everyone and the struggles to get them established were conducted with ferocious dedication and against the odds. But women trying to get away from domestic violence immediately arrived at these brand-new projects. Immediately. They had found out, somehow, that there were these other unknown women around – and that, almost out of the blue, these other women might offer assistance. And so they threw their fates to the winds to try to get help. These were acts of almost unimaginable courage at the time.

The new women’s initiatives confronted – in a concrete and undeniable way – men’s rights and power within the family. And the (male-headed) family was then the heart and bedrock of how personal, family and sexual relations were organised in society. Women were taking unprecedented action to leave their husbands who they had probably, at the time, promised to ‘obey’. They were suddenly trying to get themselves and their children out of violent marriages and partnerships, often without warning.

Not only were they doing this – extraordinary at the time – but then they were doing something even more extraordinary. They were going to live together with groups of other women in safe houses run by women. It was a quite remarkable – and entirely unpredicted -development, stunning in its fearlessness and daring.”

Gill Hague is, of course, correct, that the situation of women experiencing domestic abuse is vastly different now from that of those early refuge residents and volunteers. Her book traces the evolution of the refuge movement over the last five decades – from volunteer-run collectives to ‘professional’ service providers; from women working together to physically maintain and repair safe houses for themselves and each other, to organisations with dozens of staff, funded by government grants and contributing to policy development as experts.

Supping with the devil

As she takes the reader along that path, she often pauses to point out what has been lost as well as gained. Reflecting on the move towards funding and paid workers by the start of the 1980s, she notes that “Some feminists, like Ellen Malos, have spoken ironically of this as ‘supping with the devil’ … as radical and feminist ideas were put under pressure by the demands and restrictions imposed by funders, and by criminal justice and local authority bodies. But it seems the ‘supping’ had to be done as there had to be funding if the services were to expand and consolidate.”

Later on, it was pressure from funders again which forced a shift away from collective organising towards more formal organisational structures with CEOs, boards of trustees and the like. I have a lot of sympathy with Gill’s call to celebrate the courage and commitment of the refuge movement’s pioneers, as they created organisations that involved all workers, volunteers and residents on an equal footing. In a particularly powerful passage, she describes the impact this way of working had on the women she interviewed, who had been residents in those early, collectively run, safe houses:

“To many of them it had been transformative indeed, and they have never forgotten it. They were finally being taken seriously by others. They were listened to and could participate in decision-making. They were viewed as worthwhile members of something bigger, and their lives changed, often forever. Many previous workers felt the same. The radical politics and experiments in flattening hierarchies built a new and challenging way of working. … one previous resident … wanted it to be added, loud and clear, that the ‘over-idealistic’ argument was absolutely the opposite of her experience. To her, the equality visions of the movement had lifted her life forever after.”

He who pays the piper calls the tune

Looking at the current situation of women’s services in my local area through this historical lens, I am left feeling that we may have tipped over some kind of watershed in the last few years. What if all these cumulative encroachments and compromises have ultimately allowed those pioneering women’s accomplishments to be sold out from under us?

My local council, earlier this year, awarded a new five-year contract for women’s refuge provision to a big Housing Association, not to the women-led, grassroots charity which had built up the service from scratch, over the previous 25 years.

East Sussex County Council has also recently contracted a national Housing Association to provide refuge services.

These organisations do not share the history, principles and traditions of the women’s refuge movement. That has not stopped them from winning contracts, because the local authority funders awarding the contracts do not see those principles and traditions as important. This has been a very recent shift (at least, locally) – as recently as 2017, Brighton & Hove City Council had a comprehensive and integrated Violence against Women & Girls strategy, which recognised that:

“Violence against women and girls is a continuum: it is the basic common characteristic that underlies many different events in women and girls’ lives, involving many forms of intimate intrusion, coercion, abuse and assault, that pass into one another and cannot always be readily distinguished, but that as a continuum are used to control women and girls.” (p. 9)

The strategy was based on the expertise and analysis developed over decades by the feminist movement. This analysis was influential on a global scale, as noted in the same strategy document:

“Protection from violence against women is found in a number of International, UN and European agreements, which recognise that violence against women and girls is inextricably linked to women’s and girls’ subordinate status in society, and to an abuse of male power and privilege; and also recognise it is a function of gender inequality, and connected to the broader social, economic and cultural discrimination experienced by women.” (p. 5)

In the decade since that strategy document was drafted, this understanding seems to have been lost to our local council bureaucracies. You can scour the current draft Pan-Sussex Strategy for Domestic Abuse Accommodation and Support in vain, looking for any such clear statement of feminist principle.

Instead, we find much blander, gender-neutral statements, such as:

“Anyone can be a victim of domestic abuse, regardless of gender, age, ethnicity, religion, socio-economic status, sexuality or background.”

and

“The Government’s definition of domestic violence is ‘any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive, threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are, or have been, intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality.’”

Sex still matters

The trouble is, we haven’t come as far as our local councils seem to think. Outside the pages of their strategy documents, women are still dealing with systematic, brutal inequality. Women in abusive relationships are trapped in a series of age-old double-binds:

- they are advised and expected to end the relationship, especially if they have children (with the well-understood implication that their children may be assessed as at risk if they don’t)

- refuge provision is chronically underfunded and inadequate. According to the draft Pan-Sussex strategy, Sussex needs 171 refuge spaces for women and children, to meet the standard set by the Council of Europe. We currently have 90

- exorbitant rents, the benefit cap and the two-child limit mean that many women remain financially dependent on their abusers

- perpetrators are routinely using secretive family court processes and accusations of parental alienation to secure ongoing contact with children, binding women into lifelong contact with the men who abused them

None of these impacts is gender-neutral. But the draft strategy does not even consider sex as a factor in its list of protected characteristics.

When feminists created the first women’s refuges, their understanding of the continuum of male violence and their commitment to a meaningful process of empowerment for women led them to create spaces that were for women only. The reasons why this was important have not gone away.

But East Sussex County Council have now decided that all 47 of their previously single-sex women’s refuge places – now provided by Clarion Housing Association – will henceforth accept referrals for transwomen. This change is not subject to consultation, it is simply stated as a fait accompli in the draft Pan-Sussex strategy.

Although Brighton & Hove City Council officers assured members of the public in June this year that the city’s refuge would remain single-sex, the Equality Impact Assessment they conducted for the contract they eventually awarded to Stonewater Housing Association suggests that this may change in future, unless women speak up.

Women are rising

This weekend, the policy of our local rape crisis service, Survivors Network, to offer all its services on the basis of self-identification of gender has been criticised by many women, following an article in the Mail on Sunday. Funders and service providers who perhaps think women no longer care about feminist principles may have to revise their assessment of the situation. As we have known for a very long time, real change always comes from below.

If you live in Sussex (or even if you don’t), you can take part in the consultation on the draft strategy document until 19th December. I hope that many women who care about the legacy of those pioneering feminists will take the time to do this.

In search of evidence-based policymaking

Posted: January 16, 2021 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: brighton, gender, violence against women 2 CommentsThe UK Parliament’s Women and Equalities Select Committee is currently undertaking an inquiry into reform of the Gender Recognition Act, following the outcome of the government’s 2018 consultation on proposed changes which in turn followed the Select Committee’s 2015 inquiry into trans equality. The committee put out a call for written evidence and have also held, so far, one oral evidence session.

Looking through the written evidence that has been published, I found this submission from my local rape crisis service, Survivors’ Network.

I was already aware that Survivors’ Network, despite its origins as a grassroots feminist organisation, run by and for female survivors of sexual abuse, has in recent years adopted a policy of (to coin a phrase) ‘acceptance without exception’, under which all its women-only services are open to ‘self-identifying women’ and therefore may include male people who identify as women, as service users, staff or volunteers.

Nevertheless, I was still shocked to see an organisation which exists to respond to the devastating effects of (overwhelmingly) male violence now arguing for a review of the law which permits women to exclude male people from some services and spaces, when they have a good reason to do so.

This is a long post, in two parts, in which I try to discover what has caused this about-face.

Part 1: which came first, the policy or the evidence?

In both the evidence submission and this 2019 statement on their website, Survivors’ Network make the claim that “We know, through ground-breaking research, that trans people are disproportionately impacted by sexual violence”.

But when you click through to the research itself, it doesn’t answer (or even ask) any questions about the rates of sexual violence experienced by trans people. The high rates of sexual violence experienced by trans people are taken as adequately evidenced by other studies, and mentioned only in this scene-setting paragraph:

“Trans* individuals are often marginalised and face significant levels of abuse, harassment and violence, including sexual violence (Hill and Willoughby, 2005). More specifically, research in the United States has shown that approximately 50% of trans people experience sexual violence at some point in their lifetime (Stotzer, 2009), compared with 20% of cisgender individuals (Black et al, 2011). Moreover, the ‘Trans Mental Health Survey’ (McNeil et al, 2012), the largest survey of the trans population in the United Kingdom (UK) to date, shows that between 40 and 60% of trans people know someone in their trans community who has experienced sexual violence.”

Now, I have done a lot of detailed work, which you can read below if you feel like it, to show that this is extremely flimsy evidence for a disproportionate impact of sexual violence on trans people. But I didn’t need to go to such lengths to see that there is something very wrong with this statement.

Just read it through again and think about it. Approximately 50% of trans people experience sexual violence at some point in their lifetime. This is a distressingly high figure, I agree. Is it out of proportion with the level of sexual violence experienced by women? No.

Between 40 and 60% of trans people know someone in their trans community who has experienced sexual violence. Ask any woman if she knows a woman who has been raped or sexually assaulted. I can guarantee you the rate of positive responses will be a damn sight higher than 60%.

Compared with 20% of cisgender individuals. What? I beg your pardon? Is this piece of research, commissioned by the rape crisis service for Sussex, seriously suggesting that “cisgender individuals” is a meaningful category to use when discussing sexual violence?

Feel free to read to the end of my analysis to find out how they reached that figure of 20%, but before you do, just think about it. Sexual violence is the quintessential expression of patriarchal power. It is what holds up the whole edifice of male domination. It is a constant presence in the background of every woman’s life, from infancy. There is nothing about being “cis” that acts as a protective factor against sexual violence if you are female.

And a so-called feminist organisation is asking us to believe that it makes some kind of sense to measure sexual violence experienced by 99% of male and female people as a combined group? No.

I am, frankly, horrified that Survivors’ Network are prepared to sponsor this profoundly anti-feminist approach.

When I did the work of looking into these sources in more detail, I found that, in addition, the figures presented are far from robust. Always check the original source, kids.

So what does the Survivors’ Network research show?

In fact, the Survivors’ Network research is really about barriers for trans people accessing services. They interviewed 42 trans people who were survivors of sexual violence. These testimonies are valuable, interesting and moving, showing that trans people face a range of specific issues when accessing this kind of support.

Some findings include:

“The vast majority (83%) of respondents reported that they would feel uncomfortable accessing a service that advertises itself simply as ‘for men’ or ‘for women’”

“Over half (56%) of survivors said that it was also important or very important that the staff/volunteers at the service are also trans or non-binary, while 64% said that it would be important or very important that they were not the only trans or non-binary person using the service.”

“While it is important that existing services become more inclusive of trans people, the research also demonstrated a clear need for specialist services for trans survivors of sexual violence. Since their experience of sexual violence and their support needs are often affected by their gender identity, specialist services could offer more supportive and clearly targeted services.”

The study’s conclusion reveals the inherent tension between maintaining the feminist approach which has always underpinned sexual violence services and complying with the new ideology of infinite gender possibility:

“Service providers and policy makers need to continue highlighting the gendered nature of sexual violence (Reed et al, 2010), but they must do so in ways that do not exclude those who do not conform to the male/female gender binary. In particular, while research (Women’s Resource Centre, 2007; Sullivan, 2011) clearly demonstrates the importance of single-gender spaces in the healing process of many survivors, it is difficult to determine which individuals should have access to such spaces, given the variety of gender identities and presentations among survivors, and to what extent such spaces match the needs of an increasingly gender-diverse population (Gottschalk, 2009).”

How does the policy relate to the evidence?

In my view, there is no inherent contradiction between meeting the expressed needs of trans survivors and those of female users of single-sex support services, if providers and funders are willing to put in enough resources to do both.

This research could have been used to support the provision of sensitive specialist services to meet the specific needs of a community that is undoubtedly marginalised and in need of support. Survivors’ Network – in response to the needs identified in this research – currently offers an online support group that is specifically aimed at trans, non-binary and intersex survivors of sexual violence, for example. I’m glad this group exists.

But the much more wide-reaching impact of the policy justified by this research has been to dismantle specialist service provision for another (much larger) community – female survivors of sexual violence.

None of the services offered by Survivors’ Network now meets the needs of women who need – or would simply prefer – support in a female-only environment.

Every ‘women-only’ group or service offered by Survivors’ Network is described as open to ‘self-identifying women’. Moreover, the weekly two-hour helpline is no longer a women-only service. It’s not even a service for self-identified women, but is now for “people of any gender”.

The personal stories gathered in this research mirror those frequently told by women asking for specialist services that respect their specific experience of the trauma arising from sexual violence. Survivors’ Network used to be a place where women who needed female-only space to recover from that trauma could find the support and solidarity they needed. That option is no longer available to them.

In summary, the “groundbreaking” research commissioned and frequently cited by Survivors’ Network:

- Does not contain any new information about the rate of sexual violence experienced by trans people

- Presents research carried out into this question by other people in a misleading way to create a predetermined impression

- Contains evidence which supports specialist service provision but has been used to justify replacing specialist women-only services with services open to both sexes.

Organisations like Survivors’ Network exist because violence against women and girls is endemic in our society. They grew out of the collective determination of women to speak up for each other, to create spaces in which that violence may be reckoned with, understood, grieved over and survived, in whatever way helps each woman to find her own strength. That task is in no way complete. The need for women’s support organisations is all too persistent. Given this, I want to know why services run by and for women are seen as expendable by the trustees, managers and funders of Survivors’ Network.

Male violence damages everyone, in millions of different ways. I am not interested in excluding trans people from services they need. Not at all.

But my investigation has led me to conclude that the rape crisis service for Sussex has made an ideological commitment to meeting the needs of this community at the expense of the equally compelling needs of female survivors. When presented with a conflict between the feminism which birthed the organisation and the gender identity theory which is now dominant in the UK’s statutory and voluntary sectors, they chose to surrender their principles, along with yet another of the small, safe places created by and for women.

Part 2: Showing my workings

Is this evidence that “trans people are disproportionately impacted by sexual violence”?

“Trans* individuals are often marginalised and face significant levels of abuse, harassment and violence, including sexual violence (Hill and Willoughby, 2005). More specifically, research in the United States has shown that approximately 50% of trans people experience sexual violence at some point in their lifetime (Stotzer, 2009), compared with 20% of cisgender individuals (Black et al, 2011). Moreover, the ‘Trans Mental Health Survey’ (McNeil et al, 2012), the largest survey of the trans population in the United Kingdom (UK) to date, shows that between 40 and 60% of trans people know someone in their trans community who has experienced sexual violence.”

Supporting transgender survivors of sexual

violence: learning from users’ experiences; Sally Rymer and Valentina Cartei, on behalf of Survivors Network; Critical and Radical Social Work • vol 3 • no 1 • 155–64, 2015

Of the four studies referenced here, three use data primarily from North America. Hill and Willoughby’s work was aimed at developing a quantifiable scale and questionnaire to measure prejudice against trans and gender non-conforming people. The authors undertook three small-scale studies in order to test and calibrate their scale, concluding that “Although previous research has shown acceptance of transsexuals, these studies demonstrated that anti-trans views were neither rare nor difficult to elicit. There was a wide range of responses to the GTS scale, but some scores indicated extremely intolerant attitudes toward gender variance.”

The study was not aiming to quantify the level of abuse, harassment and violence experienced by trans people, but to develop a tool future researchers could use to understand the underlying beliefs motivating such behaviour.

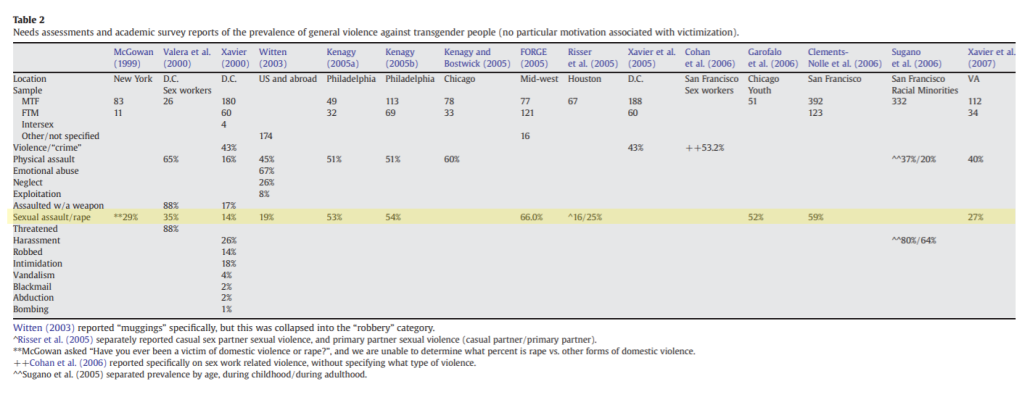

Stotzer’s research was a review of other studies into violence experienced by trans people. The author presents data from a range of self-reporting surveys, stating that “the most common finding across surveys and needs assessments is that about 50% of transgendered persons report unwanted sexual activity.”

I am not a professional researcher, and I hope readers with more relevant skills will let me know if this is an unacceptable method, but it seems to me that an alternative way to assess a range of studies like this would be to use the reported percentage from each study to calculate what percentage of all the study participants reported having experienced sexual violence. Applying that method to Stotzer’s figures, I calculated that 42% of participants in the ten studies mentioned had experienced rape or sexual violence.

Of course, whether this figure is 50% or 42%, it is undoubtedly a distressingly high proportion. But is it reasonable, as Survivors’ Network do, to compare this with a figure of 20% for “cisgender individuals”?

Comparing apples with oranges

As noted in Stotzer’s article, there are significant methodological issues relating to the use of this data: “self-report surveys often use samples that are easiest to access and the most visible, such as transgender people accessing drug rehabilitation centers, HIV/AIDS services, or who are engaged in sex work. This clearly does not reflect a representative sample of the wide variety of transgender people in the United States and around the world.”

The only UK-based research cited by Survivors’ Network is affected to some extent by the same limitations as those used in Stotzer’s study. The Trans Mental Health Survey was completed by a reasonably large but self-selecting sample of 889 people living in the UK and Ireland, recruited from “Trans support groups, online forums and mailing lists with UK members” and publicised “primarily through word-of-mouth”. The authors note that due to the impossibility of identifying the entire population of trans people, their “research relies on participants self-selecting”, and that “the sample may not be demographically representative of the trans population as a whole. In particular, the sample primarily comprised white trans people and a good proportion of those had undertaken post-Secondary education. There is no way of knowing for sure how representative this sample is.” Overall, however, they state: “While our sample is essentially one of convenience, we believe that we have fairly robust findings given the sheer size of the sample.”

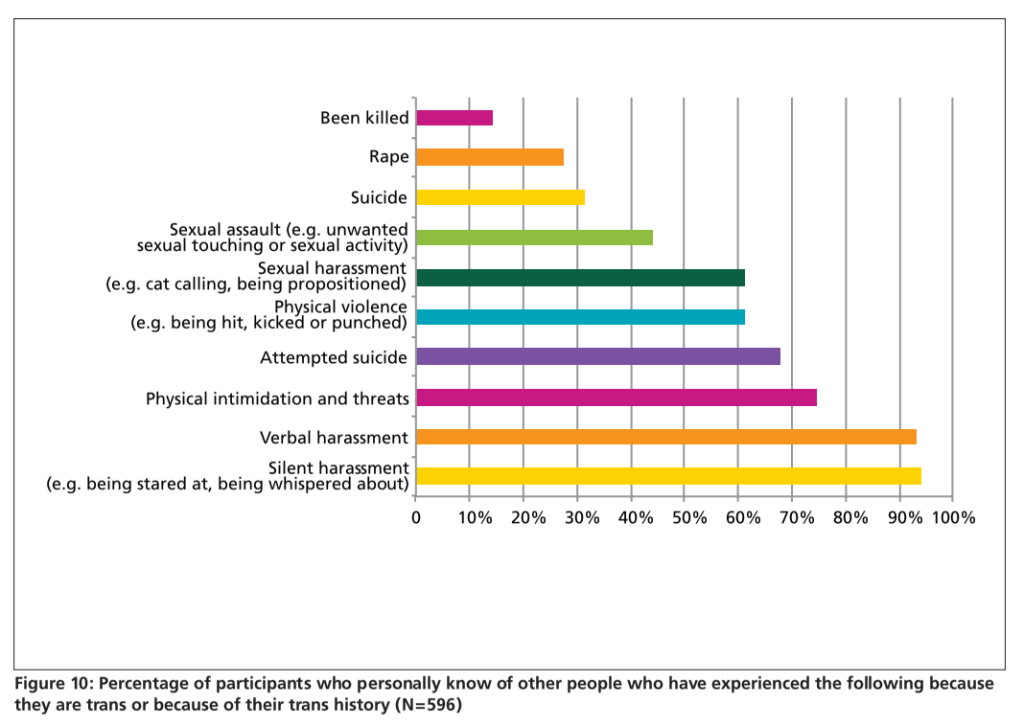

This survey did not ask a question about all experiences of sexual violence, but did ask participants whether they had been sexually assaulted or raped “because you are trans”. 14% of respondents reported having been sexually assaulted and 6% having been raped because of being trans. The percentages experiencing fear of sexual assault or rape were much higher, at 42% and 38% respectively. When asked about the experiences of other trans people, 28% said they personally knew of someone who had been raped because of being trans, and 44% said they knew someone who had been sexually assaulted because of being trans. (percentages estimated from Figure 10, reproduced below)

This appears to be the source of the Survivors Network researchers’ claim that “between 40 and 60% of trans people know someone in their trans community who has experienced sexual violence”. Presumably the range of between 40 and 60% reflects the unknown degree of overlap between these two sets of respondents.

However, especially given the recruitment methodology of this survey, these figures tell us very little about the number of trans people who have actually experienced sexual violence. We have no way of knowing how many of these respondents are thinking of the same incidents of rape and sexual assault. Given that respondents to the survey were recruited from trans community support groups and networks, it seems very likely that several participants would be aware of each incident of rape or sexual violence within this small and connected community.

This statistic has multiple issues which make it unreliable as an indicator of the prevalence of sexual violence experienced by trans people in the UK. Someone using the same method for other crimes listed here could end up suggesting that 14% of trans people have been killed because of their trans status. Fortunately, murder of trans people in the UK is in fact extremely rare. The context in which this extrapolated statistic is used in the Survivors’ Network research suggests that this is as reliable a source as their fourth study, but this is far from the case.

What about the fourth study?

The final study cited in the Survivors’ Network report is the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey 2010, carried out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA. From the report’s introduction, we learn that:

“The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey is an ongoing, nationally representative random digit dial (RDD) telephone survey that collects information about experiences of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence among non-institutionalized English and/ or Spanish-speaking women and men aged 18 or older in the United States. NISVS provides detailed information on the magnitude and characteristics of these forms of violence for the nation and for individual states.”

This is a much more robust study than the others mentioned, and should give us a reliable baseline from which to assess whether the data reported so far does describe a community that is disproportionately impacted by sexual violence.

The study found that nearly 1 in 5 women (18.3%) and 1 in 71 men (1.4%) in the United States have been raped at some time in their lives; an estimated 13% of women and 6% of men have experienced sexual coercion in their lifetime; and 27.2% of women and 11.7% of men have experienced unwanted sexual contact.

Using the same method employed by the Survivors’ Network researchers to deal with the unknown degree of overlap between these figures, we could therefore say that between 27 and 59% of US women have experienced some form of sexual violence. For men, this range is between 12 and 19%.

The Survivors’ Network report gives this study as the source for their figure of 20% of “cisgender individuals” having experienced sexual violence in their lifetimes. It appears that what they have done is to assume a complete overlap between the reported categories (ie that all of the people who reported rape and sexual coercion were included within the group who reported unwanted sexual contact), and then average the male and female percentages to reach a combined figure of 19.5%. Given the very large disparities between the rates reported by men and women in each category (over twice as many women as men have experienced each type of crime – in the case of rape, it is 13 times as many), this method serves to obscure the clearly disproportionate impact of sexual violence on women.

Sex matters in a sexist society

Posted: June 18, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: brighton, gender, nhs, violence against women 3 CommentsHere is the text of a letter I’ve sent to my MP, Caroline Lucas, following the government’s leaked announcement that they do not intend to amend the Gender Recognition Act.

Dear Caroline,

I was pleased to see reports in last weekend’s Sunday Times that the government is intending to abandon its proposed reforms of the Gender Recognition Act.

The proposals arising from the 2015 Women and Equalities Select Committee Transgender Equality Inquiry were ill-considered and developed following a flawed process in which women’s organisations were not invited to participate as witnesses.

After the government indicated its intention to implement these proposals, including changes that would have made single-sex services illegal, several grassroots womens campaigns were launched, to defend the existing provisions in the Equality Act. As a result of this campaigning, the government was forced to back down on this intention in 2018, when the consultation on GRA reforms was finally announced.

Nevertheless, many statutory institutions, companies and voluntary sector organisations had meanwhile adopted policies which made it extremely difficult for women to access single-sex provision of services. This is a real setback for women and girls who need female-only space in which to recover from, reflect on and resist the impact of living in a sexist society. As a result of organisations adopting self-id policies:

- Women in Brighton have no access to female-only support and counselling when they have been subjected to sexual assault and rape

- Girls in Brighton schools are routinely expected to share changing rooms with male pupils, and official guidance suggests that any objection to this is contrary to human rights practice

- When a woman in Brighton requested that her preference for female clinicians (resulting from her experience of being raped) be recorded in her medical notes, her request was presented as an example of transphobia in staff training materials

- Anti-feminist and unscientific concepts such as innate gender identity and sex as a spectrum are being presented as settled fact in official local authority guidance for schools

Liz Truss’s statement to the Women and Equalities Select Committee in April included a welcome commitment to protecting single-sex spaces. This echoes a similar commitment in the 2019 Labour Party manifesto, and I am pleased to see this cross-party support for the existing legal framework set out in the Equality Act. I hope you will issue a statement adding your voice to this consensus.

Sex is a protected characteristic in the Equality Act, because discrimination, harassment and abuse on the basis of sex continue to blight the lives of women and girls in the UK and around the world. It is horrifying that women who have stated this fact, such as Maya Forstater, Kathleen Stock and most recently JK Rowling, are denounced and slandered by people presenting themselves as progressive.

The government’s decision to focus on a symbolic legislative change – introducing a self-declaration basis to the GRC process – rather than any of the material issues raised during the inquiry, was unwise and divisive. Taking a step back in order to proceed in a way that upholds the rights and freedoms of women and trans people is the right thing to do.

Please convey my views to Liz Truss. I would – as ever – be pleased to discuss these issues with you in person, and look forward to receiving your response.

So it goes

Posted: June 13, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized 3 CommentsWhen I was little, I sometimes wondered if my dad was The Doctor (not a doctor, but the Doctor, from Doctor Who). It didn’t seem entirely impossible. Like Tom Baker’s time lord, he seemed to know everything. He was quick-witted, playful, questioning, interested in big stories and grand schemes, not small talk and customary habits.

If he wasn’t The Doctor, perhaps he was some other kind of alien, making the best of it after being stranded on earth – a Vulcan, perhaps, like Mr Spock. Like Spock, he was fond of the humans who were his friends, but found them all, above all else, puzzling. People were a mystery to him, but he remained curious for his whole life, finding some resonant chime in the work of other misanthropic, melancholy, mystified men – Lewis Carroll, Samuel Beckett, Bob Dylan, Ivor Cutler, James Lovelock, Kurt Vonnegut.

He was particularly taken with Vonnegut’s creation, the Tralfamadorians – four-dimensional beings who are able to see all of time laid out before them, and therefore have no conception of the beginning, middle or end of a story. When they see a person who is dead, they simply observe that he is in a bad way at that time. All the other moments of his life remain current for them.

He was fascinated by nature, admired the mathematical properties of plants and championed insects and other unappreciated creatures. He hand-reared butterfly caterpillars each year, picking them nettles from the nearby woods; and we shared our living room with several generations of giant hawk moth caterpillars, who grew so big you could hear them eating. Later in his life, he kept bees on his allotment, as his father had done on the other side of the world, a lifetime before.

Every outing was an opportunity to observe and learn. If we passed people working in the street – telephone engineers, gas repair people or building surveyors – he would very often stop and ask them what they were doing and why, much to their bemusement. He couldn’t pass a skip without having a good look through for something that might come in useful. Throwing things away was a waste, and the house, garden and garage were full of things he had rescued from this unwarranted fate.

Among my favourite playthings, for example, were several huge magnets from the back of old televisions and a jar of ball bearings. Both these wonders were rescued from the local tip, possibly at the same time, as I associate them very closely in my mind. The house was crammed full of interesting things – puzzles, games, books, newspapers, giant cardboard tubes, typewriters, a small printing press. We lived with a broken photocopier at the bottom of the stairs for several years.

He was good with his hands – always making something. He made useful things like furniture, dinners, newsletters and compost bins, but most of the things he made were intricate, beautiful mathematical models – stars, baskets, knots. He made them out of cardboard, wood, string, paper, plastic. His calculations were scribbled on the backs of envelopes and edges of newspapers. He didn’t have a shed or work room – he worked in the living room, on the floor, leaving sharp knives, hammers or pins liberally scattered around. We didn’t mind – there wasn’t a clear floor or surface in any other part of the house in any case.

We made things together too. Tablet weaving on a loom suspended from the bookshelves in the living room was my introduction to textile arts. When home computers became available, we learned together about programming. We developed slick production techniques for spray-painted posters and banners.

He was an extraordinary man, always stubbornly himself, unable to adapt or fit in, outspoken and blunt, to the point of rudeness. Adults often found him bewildering, but with children he was enchanting, sparking new connections, teasing out ideas, delighting in their discoveries and offering them the kind of focused attention that most parents and teachers don’t have time to give. I am so grateful that he was a chaotic and creative presence for both my kids, throughout their childhoods.

It was an unusual way of living, always striving to understand and make a difference in the present, keeping hold of things for future use and re-use. There was very little time for reflection. But while staying in my childhood home for the last two weeks of my father’s life, I found I could always reach out my hand and touch the past. Objects I have known for decades were sitting in their familiar places, watching us arrive at the end of his story.

I was privileged to be in the room with my dad when he breathed his last breath, and so I know that he was not a time lord. There was no immediate regeneration. As we are humans, not Tralfamadorians, we are forced to live our lives in one direction only. I am immensely sad.

My dad once described the heap of things on our kitchen surfaces as being like a very thick, boiling liquid, slowly turning things up to the top. Each individual life is a brief coincidence of cells, bubbling to the top of the thin layer of inhabitable earth, air and water on the surface of our planet. I think the best we can do is to delight in the absurd fact of being here at all, and try to honour our fellowship with all other living beings.

In memoriam, Richard Ahrens (17/10/1933 – 10/6/2020)

Fellowship is more important than leadership

Posted: April 4, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: brighton, covid 19, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, migration Leave a commentA new leader of the Labour Party has been elected today. As expected, it is Sir Keir Starmer. I didn’t vote for him, nor for any of the leadership candidates. All the candidates showed appallingly poor political judgment on an issue I happen to know something about, but mainly I couldn’t get interested in the contest at all.

After December’s election defeat, it seemed clear to me that the Labour Party had managed to stifle its own last, best hope of becoming a place where the kind of political action and understanding we need could be developed.

Starmer’s victory is being served up to us as a return to ‘sensible’ politics, with ‘grown-ups’ in charge. But it is precisely this tradition which has fed and watered the idea of the all-important leader for so many decades. Not wishing to be left out of the current trend for being shown to have been right all along, this is what I wrote in 2015, when Corbyn gained enough nominations to stand in the leadership election:

“British political culture is obsessed with leadership. Leaders are required to be visionary, charismatic, good looking, inspiring, firm but fair, correct in all things and (most crucially of all) victorious. If they miss the bar on any of these aspects, they must resign.

The fact that the Labour Party’s response to losing the election was to immediately start a process of electing a new leader is just the latest manifestation of this obsession.

…

Jeremy Corbyn is not leadership material. He is not charismatic, firm but fair, correct in all things or victorious. I will leave the question of his looks to people more qualified than I to comment. He is an inspiring speaker, who articulates a vision, shared by many people, of a world that is more just, more peaceful and more sustainable than the one we are living in now.

He is the kind of MP most people would love to have – the kind we are also blessed with here in Brighton Pavilion – a hard working, principled advocate and representative. A kind of anti-leader.”

I was frankly astonished to read this ridiculous piece by Ian Dunt this morning, bemoaning the Corbyn movement as an example of unthinking hero-worship. But as I said, this whole thing feels like a sideshow.

Back in the real (end of the) world, people are busy bringing each other food, organising street by street, providing equipment for health workers, and sharing whatever they have with those who have nothing.

None of these people waited to be told what to do by Keir Starmer, Boris Johnson or any other ‘leader’. When it comes right down to it, we all know that the people around us are what keeps us alive, not the people who think they are above us.

The health of all of us depends on the health of each of us

We have been violently reminded that we are part of an ecosystem. We should not forget it.

This perceptive piece by Jane Clare Jones draws out some of the linked lessons of the current moment: value care, accept vulnerability and abandon attempts to erect borders between us.

As she points out:

In our isolation, what becomes suddenly and starkly visible is all the life-sustaining labour that usually goes unnoticed and undervalued, much of which involves material exchange and transportation. Food distribution. Stacking shelves. Water and gas supply. Delivering post. Sewerage and rubbish collection. All the material ins and outs across the thresholds of our homes and the borders of our bodies – the mucous membranes that mark, now more than ever, our vulnerability, but keep us all alive. It’s been said, and will be said again, that we must learn our lessons here. The invisible work we hold in such low esteem is, literally, vital, and we should value it as such. The virus could enter us from animals only because we’re also animals. And like all animals, we’re materially dependent – on water, air, nutrients and the Earth.

We can’t leave people sleeping rough, or jammed together in hostels, in the middle of a pandemic. Why did we ever think we could?

We can’t expect people to follow public health advice if that leaves them without the necessities of life. So everyone must be guaranteed a basic income.

We can’t pretend that Europe’s wealth protects us from diseases, when faced with a disease spread around the world by the very same global travel and commerce that made Europe rich. Whoever grows the food you eat, whoever picks it, whoever cooks your takeaway, cleans your hospital ward or delivers your parcel is intimately connected to you. Nationality is meaningless. Making different rules for people with or without residence rights is not only cruel, it’s positively dangerous.

It won’t all be over by Christmas

Right now, we are all comforting ourselves with talk of ‘when this is over’ and ‘when things go back to normal’.

But I think we are all also haunted by the knowledge that this is not something that can be fixed quickly. Nobody knows exactly how we are going to get through this, or if that is even possible.

We do know that ‘normal’ is not something we can go back to, even if we wanted to. ‘Normal’, don’t forget, was living in a house that’s already on fire.

We now see what an emergency response looks like. We need something on at least this scale for the climate emergency.

Under pressure from below, benefit rates have increased, self-employed people have been offered some kind of safety net, and workers have had their incomes underwritten by the government.

Our local council – with extensive input from the voluntary sector and local community groups – has established a network of food hubs and a central contact point for people who need help. Public buildings are being used to pack up food parcels and repurposed as hospitals. Homeless people are being accommodated in hotels.

As the ad hoc community response becomes institutionalised, the danger of borders being recreated is very present. Support must be available to everyone, with no questions asked about immigration status or local connection.

In the meantime, those of us who are lucky enough to still have money coming in will need to continue to share with those who remain locked out.

People who call themselves leaders should take note – this crisis is making it very clear to everyone what is essential and what is not.

I am not your enemy. Let’s talk.

Posted: September 26, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: activism, brighton, gender, history, Labour Party, marriage, pride, queer, stonewall, violence against women 5 CommentsThis is the text of the speech I gave at the Woman’s Place UK fringe meeting at Labour Party conference in Brighton on 23rd September 2019. I have added links and images, but not altered the words.

I’m 50 years old. I’ve been a left wing political activist since I was 12. When I was 15 I spoke in Trafalgar Square for Youth CND, alongside a young MP called Jeremy Corbyn. I campaigned against Section 28 and helped set up Brighton Pride. I made the front pages by invading the stage at the Brighton Centre when Princess Di was welcoming a homophobic conference. I’ve had eggs thrown at me in Churchill Square and glass bottles thrown at me in London for being an out lesbian.

But I’ve never been as worried about the consequences of speaking in public about my beliefs as I am here today.

I want to talk about the division that has opened up between many feminist activists of my generation and the current queer activist movement. We should be each other’s allies, but the atmosphere is so toxic that we are hardly able to speak to each other at all.

I am worried that trans people I know and like will feel hurt and will think I am their enemy. I am not. I am worried that I will lose the friendship of people I respect in Brighton & Hove. I am worried that I will be treated as an outcast in some political circles, and that this will make it difficult for me to continue my voluntary activity in solidarity with migrants and with benefit claimants in the city.

I hope people will be prepared to hear what I have to say in good faith. I think it is possible to disagree politically while remaining courteous and respectful. I think learning from each other is more important than winning.

I am worried, but I am doing this anyway, because something has gone very wrong, and I want to be part of helping to put it right.

I’m doing this because I can’t accept that women like Helen Steel deserve to be vilified and ostracised.

Helen Steel is a woman who has spent her life standing up against the destructive power of capitalism and the state. When McDonalds tried to shut her up by suing her for libel, she took them on in an epic court case – and won – earning the lifelong admiration of many in my generation. The state tried to shut her up by sending undercover police officers into her small activist group. Helen has survived being deceived into a relationship by one of these spy cops and is still fighting for justice for herself and other women affected.

But earlier this year, because Helen has spoken out about her feminist views, she was told that her presence made people feel unsafe, and asked to leave a climate protest camp, organised by a group she helped to found. Many other excellent feminist activists have been cast out in the same way.

If you are on the left and you think women like Helen Steel are suddenly the enemy, then something has gone very wrong.

******************

My mum was a feminist of the second wave. She went to women’s liberation movement meetings in London in the early 70s and was part of the campaign to get the law changed to make sex discrimination illegal. Her generation of feminists, along with the organised labour movement, won some hugely important victories. As well as the Sex Discrimination and Equal Pay Acts, they won the right for women in most of the UK to access safe abortions, they established women’s refuges and rape crisis centres, and they paved the way for better representation of women in parliament, the media and the workforce.

When I came out at 18, it was into an activist movement that took feminist ideas seriously, and incorporated them into our practice. Brighton Area Action Against Section 28 listened to the experiences of lesbians who had broken away from the Gay Liberation Movement a decade earlier and we recognised that the way men and women are socialised means that men tend to dominate the space in mixed organisations. Therefore we made sure that our meetings were chaired by women and our campaign was represented by women in the media and on public platforms.

We rejected the Stonewall model of a paid CEO and professional lobbying, because we knew that real change comes only from below. We were one of the most active and longest-lasting local campaign groups in the movement against Section 28, and Brighton Pride emerged directly from our very political, grassroots, volunteer-run and female-led campaign.

My overwhelming memory of that time is of a feeling of freedom. Being involved in the campaign was an intensely creative and empowering experience of working collectively with other people to make new things happen and demand change. As well as discovering and establishing myself, I learned a lot about how grassroots activism can weave together the diverse experiences and skills of a community to create a sense of solidarity that is more powerful than repressive laws.

I am worried that the experience of being involved in queer activism now is not a liberating one, particularly for young women, female non-binary people and trans men. I hope I am mistaken about this.

But I have been listening to young women who have detransitioned, desisted or reidentified as women in the last few years, and one of the repeated themes of their stories is that within the trans community they felt that only only one path was available to them as they sought to understand themselves. Here are a few examples of statements I have seen from young detransitioned women, in the UK, in the last year:

“I knew I was a boy because I meet the diagnostic criteria for gender dysphoria – a strong rejection of typically feminine toys and typically feminine clothes, mostly male friends, a sense that my feelings and reactions were typical of boys, the desire to be treated as a boy. When I spoke about these experiences to older friends, or in online chat rooms, the message was affirming. Nobody encouraged the idea that it’s okay to be gender non conforming, Instead, friends and healthcare practitioners alike ‘affirmed’ my gender. Yes, you are a boy” (https://medium.com/@charlie.evans/the-medicalization-of-gender-non-conforming-children-and-the-vulnerability-of-lesbian-youth-10d4ac517e8e)

“Internalised homophobia and misogyny can play havoc on your mental state. I was a vulnerable person and I saw this one option that fit, no one talked about how dysphoria can have other causes.” (https://twitter.com/tjdetrans/status/1139505371972886530)

“I wanted to find ways of dealing with my gender issues that aren’t medically transitioning, and those ways weren’t presented to me. The only solution that was presented was chopping your breasts off, injecting yourself with hormones and becoming a man.” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7CjeGgSRBcI&t=7s)

“It’s like my entire life for seven years has been dominated by my gender dysphoria and wanting to avoid it as much as possible by Passing, so much that I stopped being myself. Now I’m realising that my life doesn’t have to be constrained by having to pass. It’s so liberating.” (https://twitter.com/detransing/status/1127265875382419456)

If you are a movement for liberation, and your female activists feel that their involvement is constraining their possibilities, then something has gone very wrong.

***************************

During the New Labour years, while I was busy with young children, Brighton Pride became more and more commercialised and less and less political. When we organised a weekend of activities around a protest march in 1991, none of us could have predicted that it would become the massive corporate spectacle it is today.

Under Stonewall’s leadership, the LGBT movement has abandoned the feminist analysis of marriage as a key site of women’s oppression, and embraced large corporations and celebrity endorsements, until our community, with its radical, creative, subversive culture has become nothing more challenging than a market segment.

Slowly, I picked up a habit of holding my tongue. Nobody wanted to hear about how marriage is bad for women when there was a gay wedding fair to go to. What was the point of reminiscing about grassroots alternatives when we seemed to have achieved mainstream acceptance?

But it seems clear to me now that because we let that silence fall, young lesbians coming out into today’s queer activist movement are cut off from the experiences of lesbian feminists who came before them. In fact, older lesbian feminists are explicitly positioned as their enemies, while massive corporations are presented as their friends.

If you are a liberation movement and you think that Barclays, Aviva, Tesco, and Proctor & Gamble are on your side, then something has gone very wrong.

*****************

When my youngest child was 11, I started writing and thinking about politics again, as the impact of the Coalition government’s austerity programme began to hit.

I was inspired by the working class women leading campaigns against the Bedroom Tax in the north of England and the young single mums of Focus E15 in London. Since 2010, at every level, austerity has hit women harder, and women have been – as usual – expected to patch up the gaps in our shredded safety net.

Some of the most important gains made by feminists of my mother’s generation are under threat. Funding cuts are leaving refuges vulnerable, while at the same time women’s options are being severely restricted by benefit cuts and caps. Women are terrified that their children will be taken into care if they stay in an abusive relationship, but denied the financial means to leave. So far in 2019, at least 72 women in the UK have been killed by men.

We still need places of safety for women. But Stonewall, in 2015, recommended to the Women and Equalities Select Committee “A review of the Equality Act 2010 to include ‘gender identity’ rather than ‘gender reassignment’ as a protected characteristic and to remove exemptions, such as access to single-sex spaces”.

Just to be crystal clear, the exemptions they are referring to are the ones which allow service providers to exclude male people from some facilities and services, even if those male people have changed their legal sex by acquiring a Gender Recognition Certificate. The example given in the Act’s explanatory notes is this:

“A group counselling session is provided for female victims of sexual assault. The organisers do not allow transsexual people to attend as they judge that the clients who attend the group session are unlikely to do so if a male-to-female transsexual person was also there. This would be lawful.”

Feminists of my mum’s generation created safe spaces for female people to escape male violence. Spaces where women could have some respite, could share their trauma with other women who would understand, could begin to heal and make their way back into the world stronger. From nothing, women built up these services and kept them going over decades.

But Stonewall would like the law changed, so that these small, safe spaces, made by women for women, are no longer permitted to exist.

Here in Brighton, even without a change in the law, our local Rape Crisis service offers no female only support groups. All their services are open to trans women, on the basis of self-identification.

I am not in any way suggesting that trans women should be denied access to support if they have been assaulted, nor that it is unreasonable for rape crisis services and women’s refuges to provide services for trans women. But I do think it is unreasonable to campaign for the removal of female only spaces, which enable traumatised women to recover from male violence.

If you are a liberation movement and you want to make it illegal for members of an oppressed group to organise independently, then something has gone very wrong.

********************

I am not an enemy of trans people. Nothing I have said this evening is an attack on trans people or a call for rights to be denied to any trans person.

All of us, in fact, have a much more dangerous enemy than each other and that is the growing threat of fascism, fuelled by catastrophic climate change.

At a moment when the human race is finally realising that we are not separate from the earth’s ecosystem, and our poisoning of the air, land and oceans is destroying our own habitat, we are already seeing how that plays out: more wars over resources, more movements of refugees across the world, and – as always in situations of conflict – more rape and trafficking of women, and intensified attempts to control our fertility.

Whatever is in store for us, as we head into the next stage of this national and global crisis, I think solidarity in diversity is going to be worth much more to all of us than the support of multinational corporations. We don’t need to flatten all distinctions between us, we don’t need to deny material reality, and we don’t need to set our minds against our bodies. Instead, we need to learn how to listen to each other and learn from each other.

That means, first of all, that everyone must acknowledge that there is a discussion to be had. We are well past the point where women will accept that our concerns are unspeakable.

The Labour Party should be facilitating this discussion. Let’s identify the common problems we are dealing with, and respectfully discuss how to tackle them. There will be areas where we disagree. It’s OK – in fact it is necessary – for people to disagree with each other. That is how we learn.

Let’s talk together about male violence. Three quarters of violent crimes and 94% of homicides are committed by male people. Feminism has many theories about why that is. I want to hear what young people think about it. I stand in solidarity with everyone who is victimised by the longstanding connection between masculinity and violence.

Let’s talk together about stereotypes and socialisation. How do children learn what it means to be a boy or a girl? What would society look like if we let go of gendered rules, roles and expectations? Does individual self-identification on a spectrum actually make a difference to the way society works?

Let’s talk together about self-organisation. I hope everyone would agree that groups of people who face oppression sometimes need exclusive spaces in which to relax, recover from, and collectively resist their oppression. I think it’s pretty clear that female people are an oppressed group, and need to be able to organise autonomously. If you disagree, let’s talk about it. Bring your argument and make your case. That’s what we do in the labour movement and in the feminist movement.

I regret that I held my tongue for such a long time. I am angry that I was intimidated into hiding my name for a year, when engaging with these issues. Women like me – like Helen Steel, like Linda Bellos, like Bea Campbell, like Julie Bindel – have every right to participate in discussion in the movements we have helped to create. We are not the enemy. Let’s talk.

Are we seeing a return of Section 28?

Posted: June 13, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: history, section 28 5 CommentsOwen Jones published a column in the Guardian this week, collating diverse examples of a backlash against LGBT people, concluding that “progress in LGBTQ rights has not simply ground to a halt, it is screeching into reverse” and invoking “the crude, unapologetic homophobia of 1980s Britain”.

As one of the people directly involved in campaigning against Section 28, back in the dark ages of 1980s Britain, I am not convinced by this comparison. The context, the sources, and the content of the antagonism Owen points to are all very different from the 1980s. I don’t think we do ourselves any favours by glossing over these differences.

1. Cultural context

In the 1980s, public opinion was heavily influenced by the mass media. The combined circulation of the Sun, Mirror and Mail in 1987 was 8.8 million. In 2019, this total has tumbled by more than half, to 3.2 million.

Newspapers back then were able to effectively whip up hysteria, with headlines like ‘save the children from sad, sordid sex lessons’ (4th June 1986) and ‘bizarre truth about happy family in the gay schoolbook’ (22nd September 1986). With no real way of fact-checking, people were willing to believe these largely fabricated stories, built on the much less sensational fact that one copy of Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin was available for teachers to borrow from the Inner London Education Authority library.

With the shift to a more fragmented media landscape, it is more difficult to gauge from media headlines whether we are seeing a rise in hostility, such as the one we saw and experienced in the late 1980s. But research shows that there has been a profound shift in public attitudes since then.

The British Social Attitudes report 34 (published in 2017) looked at trends in public opinion on a range of ‘moral issues’. They noted that homosexuality is much more widely accepted than it was 30 years ago:

“There has also been a significant increase in liberal attitudes towards same-sex relationships since the introduction of same-sex marriages in 2014; the proportion saying that same-sex relationships are ‘“not wrong at all’” is now a clear majority at 64%, up from 59% in 2015, and 47% in 2012. Looking further back to when the question was first asked in the 1980s an even starker picture emerges. In 1983 only 17% were completely accepting of same-sex relationships. Attitudes hardened further during the late 1980s at the height of the AIDS crisis; in 1987 just 11% said same-sex relationships were “not wrong at all”. At that time three-quarters (74%) of British people thought same-sex relationships were “always” or “mostly” wrong, a view that has fallen to 19% today.”

2. If you’re not with us…

Owen identifies a range of actors, lumping them all together as aspects of “the current threat facing LGBTQ people”:

- “homophobic protesters” campaigning against the No Outsiders programme in Birmingham schools, with the support of a local Labour MP.

- Esther McVey, suggesting that parents should be able to withdraw their children from sex & relationship education.

- Ann Widdecombe, raising the possibility of science finding “an answer” to homosexuality.

- the attackers of the lesbian couple who were beaten on a London bus, and the perpetrators of ‘hate crimes’ more generally

- Donald Trump, taking legislative action against trans people in the US military

- “Anti trans activists” and “much of the media” whose “tawdry, sinister campaign” “demonises” trans people and “legitimises and fuels” hatred and violence against them.

I am not convinced that this list adds up to the kind of concerted, state-backed campaign of hostility that we faced in the 1980s. In particular, I think Owen’s instruction at the end of the piece to “join the dots” is an unhelpful fabrication of alliances that do not exist.

There were indeed parents who campaigned against the alleged ‘promotion of homosexuality’ in Haringey schools in the 1980s. As now, their motivations were a complex mix of religious faith, prejudice and parental concern for the wellbeing of their children. But the Haringey parents in the 1980s had the backing of the government, mass media and public opinion, while today the parents in Birmingham are firmly outside the mainstream.

In the 1980s, Haringey Council’s Positive Images policy became mired in controversy and was eventually squashed by the introduction of Section 28 before it could even be fully articulated, let alone implemented (see this fascinating PhD thesis for the full story). The parents and politicians campaigning against it were largely opposing something of their own invention, while the council insisted that it was to be nothing more challenging than an explanation that gay people exist and discrimination is hurtful.

On the other hand, the No Outsiders programme is being delivered in schools, and it contains some concepts and ideas that I find troubling. I am reluctant to simply condemn the protests as homophobic.

In particular, I am unhappy with the presentation to primary school children of the notion of innate gender identity and the idea that sex is assigned (rather than observed) at birth.

Owen claims that Esther McVey’s comments help “shift the political conversation, reopening debates that were supposed to have been settled long ago, reviving the phantom of section 28.” I must say, the article he links to, in which a parade of senior Tories line up to disagree with her and affirm their support for same-sex marriage, is somewhat weak evidence for this idea. In 1992, we couldn’t even get the Labour administration of Brighton Council to publicly defend their own decision to give us a grant of £5,000 for our fledgling Pride event. I think the political conversation has moved on quite far.

Anne Widdecombe’s comments, quoted in the piece Owen links to, are interesting, in fact. She said:

“there was a time when we thought it was quite impossible for men to become women and vice versa and the fact that we now think it is quite impossible for people to switch sexuality doesn’t mean that science may not be able to produce an answer at some stage.”

I was always wary, back in the day, of the insistence that homosexuality must be innate and of biological origin. I feared that it could lead precisely in this direction, towards the idea that if only the ‘gay gene’ could be discovered, it could be eliminated. I preferred to argue that homosexuality was not a problem that needed solving, and that its cause was therefore not something that needed to be figured out. I wonder if our “side” having wholeheartedly embraced a ‘born this way’ narrative for both sexual orientation and gender identity has been a tactical error, after all.

Unlike the rest of the cast assembled in this piece, Owen’s “anti trans campaigners” turn out to be feminists like Julie Bindel and Womans Place UK. Here, I have a real problem with the argument he is making.

3. Dots that don’t join up

Owen claims that the pressure on the NSPCC to drop Munroe Bergdorf as a face of Childline was motivated by a wish to “drive trans people out of public life”. But the reason given by the NSPCC was that:

“The board decided an ongoing relationship with Munroe was inappropriate because of her statements on the public record, which we felt would mean that she was in breach of our own risk assessments and undermine what we are here to do. These statements are specific to safeguarding and equality.”

They haven’t explained what they are referring to, but if you read this thread on Mumsnet, you can see the concerns emerging as women discuss why they find this appointment inappropriate. First, there is Munroe’s public backing for the 11 year old “drag kid” Desmond Is Amazing and her lack of concern about Desmond’s immersion in an adult and sexualised art form. Then there’s the issue of Munroe having encouraged “trans kids” to contact her privately on Twitter and Instagram.

These concerns about Munroe’s lack of awareness of basic safeguarding are not about driving trans people out of public life. They are about whether she is a suitable person to represent a children’s safeguarding charity.

Owen’s final example is this:

“The anti-trans activists who hounded Bergdorf are now demanding the sacking of a senior, gay NSPCC employee because they found pictures of him in fetish gear online, suggesting therefore he is not safe around children. This is the crude, unapologetic homophobia of 1980s Britain.”

But it wasn’t just pictures. It was a video, which the employee in question had published, showing himself in rubber underwear, masturbating in his workplace toilets.

Now, I don’t care what people do in their own time. But I think women raising questions about the judgment of somebody who thinks it’s OK to engage in exhibitionist fetish play while at work in a children’s charity is not remotely comparable to the unapologetic homophobia of the 1980s, and frankly I find it a bit insulting for Owen to suggest that it is.

We were up against a powerful mass media, the whole political establishment and the law of the land. We were living in a country where three quarters of the population thought being gay was always or mostly wrong. We were living through an epidemic that was killing young gay men and coping with the stigmatisation of our community as carriers of disease. Lesbians were scared of losing their children, many of us were scared of losing our jobs, just for coming out. We were fighting for basic human rights, not the freedom to have a wank at work and share it on the internet.

Prominent campaigners like Owen Jones appearing to defend inappropriate behaviour at work because the person concerned is gay seems to me to be entirely counterproductive.

Mumsnet’s feminism chat board is not in league with Donald Trump, Anne Widdecombe or Esther McVey. Julie Bindel is not causing a rise in violence against LGBT people (quite the opposite).

Women who have spent decades fighting for feminist and left-wing causes are not leaping into bed with the evangelical right, and it is really unhelpful to pretend that they are.

The history of Section 28 is important, but it’s not the only story we can ever tell about LGBT rights. Many of the people now sounding the alarm about the direction of the movement are veterans of that campaign. Pretending that they are somehow in league with homophobes is a misleading and unworthy way to avoid confronting a real difference of opinion on the left. We can do better than that.

Papers, please

Posted: April 6, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: history, migration, nhs Leave a commentI have been puzzled by the sudden rise in deportations and Home Office attacks on black people who have been in UK for decades, such as the case of Albert Thompson, which I wrote about a few weeks ago, or the many similar cases now coming to light.

These people are not the stated target of the “hostile environment for illegal immigrants”, so why are they being picked on?

It’s not to appease a racist public – as far as I can see from reading online discussion of these cases, most people are convinced that they are a mistake. There is not widespread support for this action, or understanding that it is a direct consequence of current government policy which has turned landlords, hospital administrators, employers and bank managers into border guards.

I don’t believe the aim is to remove significant numbers of black people from the UK. Most of the people affected are parents and grandparents of British citizens. If the government were trying to stop them from becoming an integrated part of UK communities, they would surely have done it a long time ago.

It’s also unlikely to be pure sadism and cruelty, though I can see why it would appear that way to the families affected.

The Home Office isn’t yet staffed by robots, as far as I know – people are making these decisions. Even if the ‘hostile environment’ regulations seem to dictate the actions that are being taken, there could have been a management decision not to persecute this group of people who are clearly not, by any stretch of the imagination, “illegal immigrants”. (I am leaving aside for now the issue of the equally unjust impact of these new laws on people who are considered “illegal”, but that doesn’t mean that I think any of this is OK.)

So I was puzzled. But I recently came across a clue when I read about the government’s attempts to rebrand the ‘hostile environment’ as a ‘compliant environment’.

My theory now is that this is an example of an age-old trick of the ruling class – extend your power by testing out a previously unacceptable imposition on a disposable population, then rely on it being a fait accompli to persuade everyone it was always inevitable.

Liberty’s 2015 briefing for MPs on the issue of immigration detention explains how this kind of mission creep works:

Immigration detention has become such a policy mainstay, it is easy to forget what a constitutional novelty it was when powers to administratively detain were first set out in the Immigration Act 1971. In a move unprecedented in peacetime Britain, the Act reversed the principle of habeas corpus, removing the onus from the state to justify the deprivation of liberty, and introducing administrative detention for those subject to deportation. In the intervening decades, the use of detention has evolved from a mechanism designed to enforce removal or examination, to a free-standing immigration power routinely exercised for administrative convenience.

The hostile environment itself is a quintessential example – across all the areas where it acts to make life difficult for migrants, the core idea is that individuals must be prepared to justify themselves to authority on demand.

If you want to rent somewhere to live, receive hospital treatment or maintain a bank account, you must now prove that you have a legal right to reside in the UK. This means it is up to the individual to have their papers in order and present them to all kinds of people in order to do all kinds of ordinary things.

When I read online discussion about the cases of Caribbean elders now facing deportation, detention or denial of healthcare, there are a few people who present this as a reasonable expectation. Why have they not sorted out their documents, if they have been here all this time?

If they been here for so long why have they not applied for citizenship!!

— Tony (@VetteheadTony) April 1, 2018

Get real… You’re talking about people who in 40+years haven’t managed to get any documentation….

One person you give is trying to use a birth cert with a different name on it to get a passport – and they wonder why it was rejected! FFS….

Unbelievable.

— Martin Dooley (@martindooley) April 1, 2018

The idea of individuals being accountable to the state has already been thoroughly tested on another disposable population – unemployed people and people who are too sick or disabled to work. And just as the hostile environment is now being extended to people who are British for all practical purposes, Universal Credit extends the sanctions and testing regime to people who have so far been exempt from the label of scrounger.

People on low wages and self-employed people are among those hit most hard by the bizarre workings of Universal Credit. Not so long ago, these were the people championed by Theresa May’s party as strivers and entrepreneurs. Now, they have joined the ranks of those who are expected to show compliance to the demands of the all-powerful work coach.

By stealth, the whole way we look at things becomes inverted. Just as with the bedroom tax back in 2013, the most powerful and long-lasting effect of these vicious policies is not the impact on those directly affected, but the way they retrain all of us to think about public services.

So once we have become used to the idea that even people who arrived in the UK as children, as British citizens by virtue of the colonisation of their native countries by the British, must prove themselves if they wish to be treated with anything resembling respect, what next? Who is next in the firing line?

An excellent recent thread on Twitter by Docs not Cops points out that we are already a fair way down the road towards declaring some people ‘undeserving’ of free NHS care. And of course, the hostile environment also provides fertile ground – and the practical infrastructure – for the introduction of widespread charging in the NHS. This result has been a long time in the making – Nye Bevan issued a very precise warning about it as long ago as 1952.

But these ideas are not inevitable. It is possible to change the direction of travel. The revelations about Facebook’s data breaches have opened up the issue of privacy in a way that I didn’t really expect to see again. These questions of accountability are the key battleground for the future of our public services. Are we residents with rights that derive from our humanity, or subjects who must prove our conditional entitlement? How do we redesign our public services to recognise our interdependence, our need for mutual support and care, and the contribution everyone makes to our complex society?

A little story about white privilege

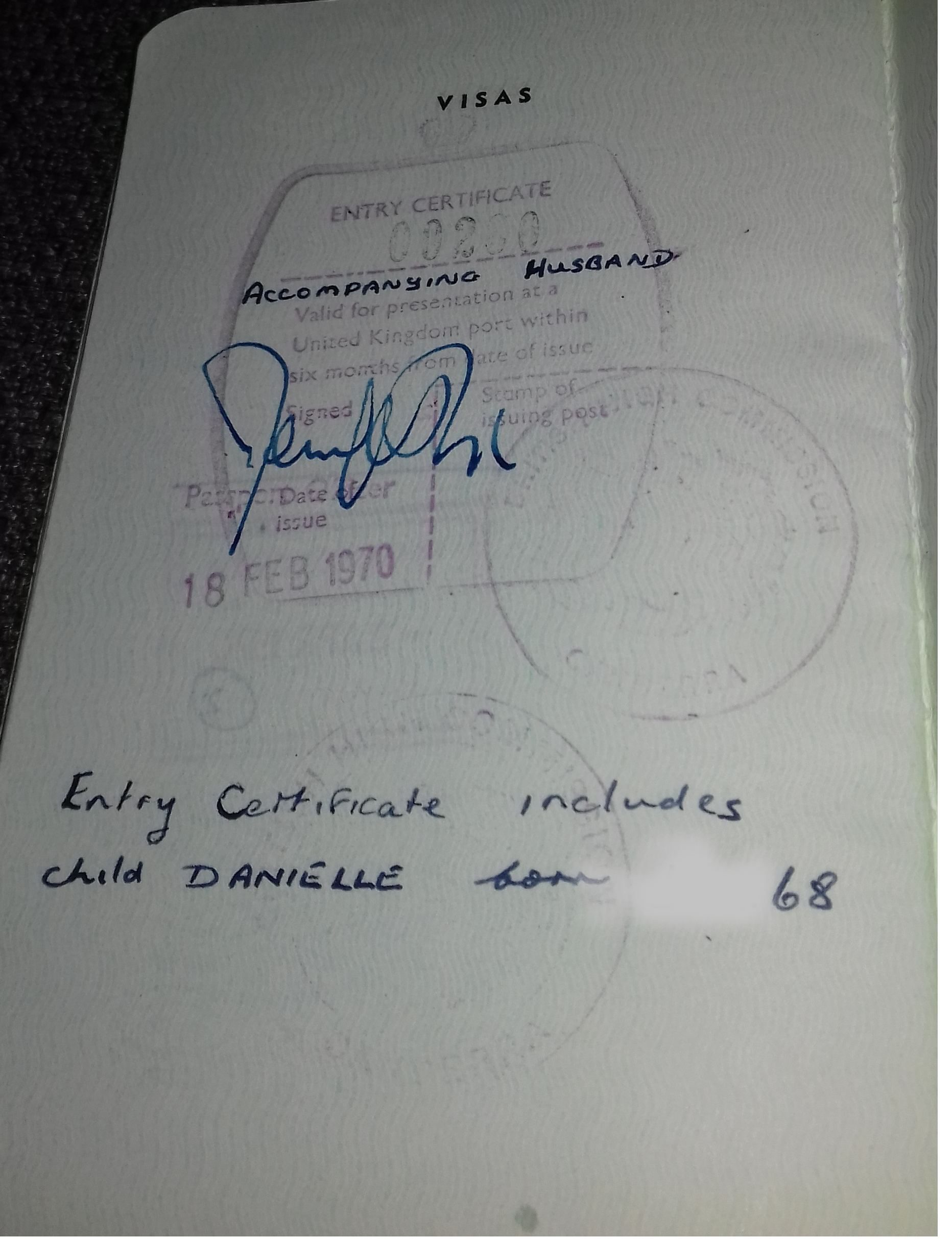

Posted: March 11, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: history, migration, nhs 3 CommentsIn the 1960s, many people arrived in the UK from its former colonies in the Caribbean. They were encouraged and welcomed by the British government, as workers in the growing public sector. [Edit: I have learned from a very informative and referenced Twitter thread published by Akala on 1st April 2018 that this is a myth, and that all postwar British governments implemented racist and exclusionary policies towards black people who migrated to the UK.]

Albert Thompson’s mother was one of these people. While she worked in the NHS, her son was left behind in Jamaica. I can only imagine how hard that must have been for both of them. Lucky me.

My parents arrived in the UK in 1970. Like Mr. Thompson’s mother, they were entitled to enter and stay in the UK as Commonwealth citizens. They brought their child with them.